The Hitchhiker's Guide to Concurrency

Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable beginning of the 21st century lies a small subset of human knowledge.

Within this subset of human knowledge is an utterly insignificant little discipline whose Von Neumann-descended architecture is so amazingly primitive that it is still thought that RPN calculators are a pretty neat idea.

This discipline has — or rather had — a problem, which was this: most of the people studying it were unhappy for pretty much of the time when trying to write parallel software. Many solutions were suggested for this problem, but most of these were largely concerned with the handling of little pieces of logic called locks and mutexes and whatnot, which is odd because on the whole it wasn't the small pieces of logic that needed parallelism.

And so the problem remained; lots of people were mean, and most of them were miserable, even those with RPN calculators.

Many were increasingly of the opinion that they'd all made a big mistake in trying to add parallelism to their programming languages, and that no program should have ever left its initial thread.

Note: parodying The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is fun. Read the book if you haven't already. It's good!

Don't Panic

Hi. Today (or whatever day you are reading this, even tomorrow), I'm going to tell you about concurrent Erlang. Chances are you've read about or dealt with concurrency before.  You might also be curious about the emergence of multi-core programming. Anyway, the probabilities are high that you're reading this book because of all this talk about concurrency going on these days.

You might also be curious about the emergence of multi-core programming. Anyway, the probabilities are high that you're reading this book because of all this talk about concurrency going on these days.

A warning though; this chapter is mostly theoric. If you have a headache, a distaste for programming language history or just want to program, you might be better off skipping to the end of the chapter or skip to the next one (where more practical knowledge is shown.)

I've already explained in the book's intro that Erlang's concurrency was based on message passing and the actor model, with the example of people communicating with nothing but letters. I'll explain it more in details again later, but first of all, I believe it is important to define the difference between concurrency and parallelism.

In many places both words refer to the same concept. They are often used as two different ideas in the context of Erlang. For many Erlangers, concurrency refers to the idea of having many actors running independently, but not necessarily all at the same time. Parallelism is having actors running exactly at the same time. I will say that there doesn't seem to be any consensus on such definitions around various areas of computer science, but I will use them in this manner in this text. Don't be surprised if other sources or people use the same terms to mean different things.

This is to say Erlang had concurrency from the beginning, even when everything was done on a single core processor in the '80s. Each Erlang process would have its own slice of time to run, much like desktop applications did before multi-core systems.

Parallelism was still possible back then; all you needed to do was to have a second computer running the code and communicating with the first one. Even then, only two actors could be run in parallel in this setup. Nowadays, multi-core systems allows for parallelism on a single computer (with some industrial chips having many dozens of cores) and Erlang takes full advantage of this possibility.

Don't drink too much Kool-Aid:

The distinction between concurrency and parallelism is important to make, because many programmers hold the belief that Erlang was ready for multi-core computers years before it actually was. Erlang was only adapted to true symmetric multiprocessing in the mid 2000s and only got most of the implementation right with the R13B release of the language in 2009. Before that, SMP often had to be disabled to avoid performance losses. To get parallelism on a multicore computer without SMP, you'd start many instances of the VM instead.

An interesting fact is that because Erlang concurrency is all about isolated processes, it took no conceptual change at the language level to bring true parallelism to the language. All the changes were transparently done in the VM, away from the eyes of the programmers.

Concepts of Concurrency

Back in the day, Erlang's development as a language was extremely quick with frequent feedback from engineers working on telephone switches in Erlang itself. These interactions proved processes-based concurrency and asynchronous message passing to be a good way to model the problems they faced. Moreover, the telephony world already had a certain culture going towards concurrency before Erlang came to be. This was inherited from PLEX, a language created earlier at Ericsson, and AXE, a switch developed with it. Erlang followed this tendency and attempted to improve on previous tools available.

Erlang had a few requirements to satisfy before being considered good. The main ones were being able to scale up and support many thousands of users across many switches, and then to achieve high reliability—to the point of never stopping the code.

Scalability

I'll focus on the scaling first. Some properties were seen as necessary to achieve scalability. Because users would be represented as processes which only reacted upon certain events (i.e.: receiving a call, hanging up, etc.), an ideal system would support processes doing small computations, switching between them very quickly as events came through. To make it efficient, it made sense for processes to be started very quickly, to be destroyed very quickly and to be able to switch them really fast. Having them lightweight was mandatory to achieve this. It was also mandatory because you didn't want to have things like process pools (a fixed amount of processes you split the work between.) Instead, it would be much easier to design programs that could use as many processes as they need.

Another important aspect of scalability is to be able to bypass your hardware's limitations. There are two ways to do this: make the hardware better, or add more hardware. The first option is useful up to a certain point, after which it becomes extremely expensive (i.e.: buying a super computer). The second option is usually cheaper and requires you to add more computers to do the job. This is where distribution can be useful to have as a part of your language.

Anyway, to get back to small processes, because telephony applications needed a lot of reliability, it was decided that the cleanest way to do things was to forbid processes from sharing memory. Shared memory could leave things in an inconsistent state after some crashes (especially on data shared across different nodes) and had some complications. Instead, processes should communicate by sending messages where all the data is copied. This would risk being slower, but safer.

Fault-tolerance

This leads us on the second type of requirements for Erlang: reliability. The first writers of Erlang always kept in mind that failure is common. You can try to prevent bugs all you want, but most of the time some of them will still happen. In the eventuality bugs don't happen, nothing can stop hardware failures all the time. The idea is thus to find good ways to handle errors and problems rather than trying to prevent them all.

It turns out that taking the design approach of multiple processes with message passing was a good idea, because error handling could be grafted onto it relatively easily. Take lightweight processes (made for quick restarts and shutdowns) as an example. Some studies proved that the main sources of downtime in large scale software systems are intermittent or transient bugs (source). Then, there's a principle that says that errors which corrupt data should cause the faulty part of the system to die as fast as possible in order to avoid propagating errors and bad data to the rest of the system. Another concept here is that there exist many different ways for a system to terminate, two of which are clean shutdowns and crashes (terminating with an unexpected error).

Here the worst case is obviously the crash. A safe solution would be to make sure all crashes are the same as clean shutdowns: this can be done through practices such as shared-nothing and single assignment (which isolates a process' memory), avoiding locks (a lock could happen to not be unlocked during a crash, keeping other processes from accessing the data or leaving data in an inconsistent state) and other stuff I won't cover more, but were all part of Erlang's design. Your ideal solution in Erlang is thus to kill processes as fast as possible to avoid data corruption and transient bugs. Lightweight processes are a key element in this. Further error handling mechanisms are also part of the language to allow processes to monitor other processes (which are described in the Errors and Processes chapter), in order to know when processes die and to decide what to do about it.

Supposing restarting processes real fast is enough to deal with crashes, the next problem you get is hardware failures. How do you make sure your program keeps running when someone kicks the computer it's running on?  Although a fancy defense mechanism comprising laser detection and strategically placed cacti could do the job for a while, it would not last forever. The hint is simply to have your program running on more than one computer at once, something that was needed for scaling anyway. This is another advantage of independent processes with no communication channel outside message passing. You can have them working the same way whether they're local or on a different computer, making fault tolerance through distribution nearly transparent to the programmer.

Although a fancy defense mechanism comprising laser detection and strategically placed cacti could do the job for a while, it would not last forever. The hint is simply to have your program running on more than one computer at once, something that was needed for scaling anyway. This is another advantage of independent processes with no communication channel outside message passing. You can have them working the same way whether they're local or on a different computer, making fault tolerance through distribution nearly transparent to the programmer.

Being distributed has direct consequences on how processes can communicate with each other. One of the biggest hurdles of distribution is that you can't assume that because a node (a remote computer) was there when you made a function call, it will still be there for the whole transmission of the call or that it will even execute it correctly. Someone tripping over a cable or unplugging the machine would leave your application hanging. Or maybe it would make it crash. Who knows?

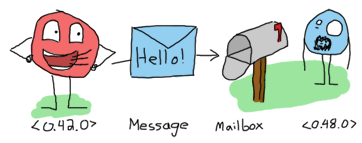

Well it turns out the choice of asynchronous message passing was a good design pick there too. Under the processes-with-asynchronous-messages model, messages are sent from one process to a second one and stored in a mailbox inside the receiving process until they are taken out to be read. It's important to mention that messages are sent without even checking if the receiving process exists or not because it would not be useful to do so. As implied in the previous paragraph, it's impossible to know if a process will crash between the time a message is sent and received. And if it's received, it's impossible to know if it will be acted upon or again if the receiving process will die before that. Asynchronous messages allow safe remote function calls because there is no assumption about what will happen; the programmer is the one to know. If you need to have a confirmation of delivery, you have to send a second message as a reply to the original process. This message will have the same safe semantics, and so will any program or library you build on this principle.

Implementation

Alright, so it was decided that lightweight processes with asynchronous message passing were the approach to take for Erlang. How to make this work? Well, first of all, the operating system can't be trusted to handle the processes. Operating systems have many different ways to handle processes, and their performance varies a lot. Most if not all of them are too slow or too heavy for what is needed by standard Erlang applications. By doing this in the VM, the Erlang implementers keep control of optimization and reliability. Nowadays, Erlang's processes take about 300 words of memory each and can be created in a matter of microseconds—not something doable on major operating systems these days.

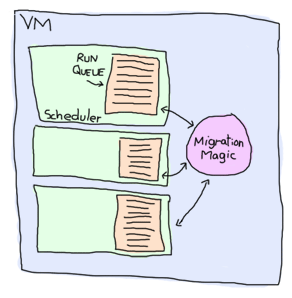

To handle all these potential processes your programs could create, the VM starts one thread per core which acts as a scheduler. Each of these schedulers has a run queue, or a list of Erlang processes on which to spend a slice of time. When one of the schedulers has too many tasks in its run queue, some are migrated to another one. This is to say each Erlang VM takes care of doing all the load-balancing and the programmer doesn't need to worry about it. There are some other optimizations that are done, such as limiting the rate at which messages can be sent on overloaded processes in order to regulate and distribute the load.

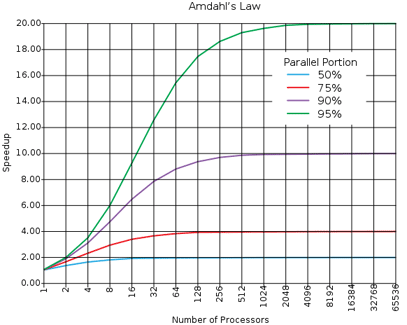

All the hard stuff is in there, managed for you. That is what makes it easy to go parallel with Erlang. Going parallel means your program should go twice as fast if you add a second core, four times faster if there are 4 more and so on, right? It depends. Such a phenomenon is named linear scaling in relation to speed gain vs. the number of cores or processors (see the graph below.) In real life, there is no such thing as a free lunch (well, there are at funerals, but someone still has to pay, somewhere).

Not Entirely Unlike Linear Scaling

The difficulty of obtaining linear scaling is not due to the language itself, but rather to the nature of the problems to solve. Problems that scale very well are often said to be embarrassingly parallel. If you look for embarrassingly parallel problems on the Internet, you're likely to find examples such as ray-tracing (a method to create 3D images), brute-forcing searches in cryptography, weather prediction, etc.

From time to time, people then pop up in IRC channels, forums or mailing lists asking if Erlang could be used to solve that kind of problem, or if it could be used to program on a GPU. The answer is almost always 'no'. The reason is relatively simple: all these problems are usually about numerical algorithms with lots of data crunching. Erlang is not very good at this.

Erlang's embarrassingly parallel problems are present at a higher level. Usually, they have to do with concepts such as chat servers, phone switches, web servers, message queues, web crawlers or any other application where the work done can be represented as independent logical entities (actors, anyone?). This kind of problem can be solved efficiently with close-to-linear scaling.

Many problems will never show such scaling properties. In fact, you only need one centralized sequence of operations to lose it all. Your parallel program only goes as fast as its slowest sequential part. An example of that phenomenon is observable any time you go to a mall. Hundreds of people can be shopping at once, rarely interfering with each other. Then once it's time to pay, queues form as soon as there are fewer cashiers than there are customers ready to leave.

It would be possible to add cashiers until there's one for each customer, but then you would need a door for each customer because they couldn't get inside or outside the mall all at once.

To put this another way, even though customers could pick each of their items in parallel and basically take as much time to shop whether they're alone or a thousand in the store, they would still have to wait to pay. Therefore their shopping experience can never be shorter than the time it takes them to wait in the queue and pay.

A generalisation of this principle is called Amdahl's Law. It indicates how much of a speedup you can expect your system to have whenever you add parallelism to it, and in what proportion:

According to Amdahl's law, code that is 50% parallel can never get faster than twice what it was before, and code that is 95% parallel can theoretically be expected to be about 20 times faster if you add enough processors. What's interesting to see on this graph is how getting rid of the last few sequential parts of a program allows a relatively huge theoretical speedup compared to removing as much sequential code in a program that is not very parallel to begin with.

Don't drink too much Kool-Aid:

Parallelism is not the answer to every problem. In some cases, going parallel will even slow down your application. This can happen whenever your program is 100% sequential, but still uses multiple processes.

One of the best examples of this is the ring benchmark. A ring benchmark is a test where many thousands of processes will pass a piece of data to one after the other in a circular manner. Think of it as a game of telephone if you want. In this benchmark, only one process at a time does something useful, but the Erlang VM still spends time distributing the load accross cores and giving every process its share of time.

This plays against many common hardware optimizations and makes the VM spend time doing useless stuff. This often makes purely sequential applications run much slower on many cores than on a single one. In this case, disabling symmetric multiprocessing ($ erl -smp disable) might be a good idea.

So long and thanks for all the fish!

Of course, this chapter would not be complete if it wouldn't show the three primitives required for concurrency in Erlang: spawning new processes, sending messages, and receiving messages. In practice there are more mechanisms required for making really reliable applications, but for now this will suffice.

I've skipped around the issue a whole lot and I have yet to explain what a process really is. It's in fact nothing but a function. That's it. It runs a function and once it's done, it disappears. Technically, a process also has some hidden state (such as a mailbox for messages), but functions are enough for now.

To start a new process, Erlang provides the function spawn/1, which takes a single function and runs it:

1> F = fun() -> 2 + 2 end. #Fun<erl_eval.20.67289768> 2> spawn(F). <0.44.0>

The result of spawn/1 (<0.44.0>) is called a Process Identifier, often just written PID, Pid, or pid by the community. The process identifier is an arbitrary value representing any process that exists (or might have existed) at some point in the VM's life. It is used as an address to communicate with the process.

You'll notice that we can't see the result of the function F. We only get its pid. That's because processes do not return anything.

How can we see the result of F then? Well, there are two ways. The easiest one is to just output whatever we get:

3> spawn(fun() -> io:format("~p~n",[2 + 2]) end).

4

<0.46.0>

This isn't practical for a real program, but it is useful for seeing how Erlang dispatches processes. Fortunately, using io:format/2 is enough to let us experiment. We'll start 10 processes real quick and pause each of them for a while with the help of the function timer:sleep/1, which takes an integer value N and waits for N milliseconds before resuming code. After the delay, the value present in the process is output.

4> G = fun(X) -> timer:sleep(10), io:format("~p~n", [X]) end.

#Fun<erl_eval.6.13229925>

5> [spawn(fun() -> G(X) end) || X <- lists:seq(1,10)].

[<0.273.0>,<0.274.0>,<0.275.0>,<0.276.0>,<0.277.0>,

<0.278.0>,<0.279.0>,<0.280.0>,<0.281.0>,<0.282.0>]

2

1

4

3

5

8

7

6

10

9

The order doesn't make sense. Welcome to parallelism. Because the processes are running at the same time, the ordering of events isn't guaranteed anymore. That's because the Erlang VM uses many tricks to decide when to run a process or another one, making sure each gets a good share of time. Many Erlang services are implemented as processes, including the shell you're typing in. Your processes must be balanced with those the system itself needs and this might be the cause of the weird ordering.

Note: the results are similar whether symmetric multiprocessing is enabled or not. To prove it, you can just test it out by starting the Erlang VM with $ erl -smp disable.

To see if your Erlang VM runs with or without SMP support in the first place, start a new VM without any options and look for the first line output. If you can spot the text [smp:2:2] [rq:2], it means you're running with SMP enabled, and that you have 2 run queues (rq, or schedulers) running on two cores. If you only see [rq:1], it means you're running with SMP disabled.

If you wanted to know, [smp:2:2] means there are two cores available, with two schedulers. [rq:2] means there are two run queues active. In earlier versions of Erlang, you could have multiple schedulers, but with only one shared run queue. Since R13B, there is one run queue per scheduler by default; this allows for better parallelism.

To prove the shell itself is implemented as a regular process, I'll use the BIF self/0, which returns the pid of the current process:

6> self(). <0.41.0> 7> exit(self()). ** exception exit: <0.41.0> 8> self(). <0.285.0>

And the pid changes because the process has been restarted. The details of how this works will be seen later. For now, there's more basic stuff to cover. The most important one right now is to figure out how to send messages around, because nobody wants to be stuck with outputting the resulting values of processes all the time, and then entering them by hand in other processes (at least I know I don't.)

The next primitive required to do message passing is the operator !, also known as the bang symbol. On the left-hand side it takes a pid and on the right-hand side it takes any Erlang term. The term is then sent to the process represented by the pid, which can access it:

9> self() ! hello. hello

The message has been put in the process' mailbox, but it hasn't been read yet. The second hello shown here is the return value of the send operation. This means it is possible to send the same message to many processes by doing:

10> self() ! self() ! double. double

Which is equivalent to self() ! (self() ! double). A thing to note about a process' mailbox is that the messages are kept in the order they are received. Every time a message is read it is taken out of the mailbox. Again, this is a bit similar to the introduction's example with people writing letters.

To see the contents of the current mailbox, you can use the flush() command while in the shell:

11> flush(). Shell got hello Shell got double Shell got double ok

This function is just a shortcut that outputs received messages. This means we still can't bind the result of a process to a variable, but at least we know how to send it from a process to another one and check if it's been received.

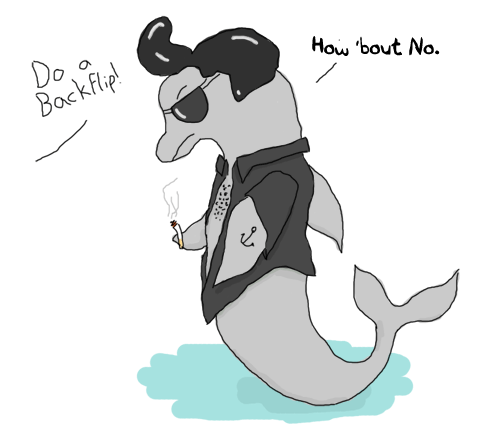

Sending messages that nobody will read is as useful as writing emo poetry; not a whole lot. This is why we need the receive statement. Rather than playing for too long in the shell, we'll write a short program about dolphins to learn about it:

-module(dolphins).

-compile(export_all).

dolphin1() ->

receive

do_a_flip ->

io:format("How about no?~n");

fish ->

io:format("So long and thanks for all the fish!~n");

_ ->

io:format("Heh, we're smarter than you humans.~n")

end.

As you can see, receive is syntactically similar to case ... of. In fact, the patterns work exactly the same way except they bind variables coming from messages rather than the expression between case and of. Receives can also have guards:

receive

Pattern1 when Guard1 -> Expr1;

Pattern2 when Guard2 -> Expr2;

Pattern3 -> Expr3

end

We can now compile the above module, run it, and start communicating with dolphins:

11> c(dolphins).

{ok,dolphins}

12> Dolphin = spawn(dolphins, dolphin1, []).

<0.40.0>

13> Dolphin ! "oh, hello dolphin!".

Heh, we're smarter than you humans.

"oh, hello dolphin!"

14> Dolphin ! fish.

fish

15>

Here we introduce a new way of spawning with spawn/3. Rather than taking a single function, spawn/3 takes the module, function and its arguments as its own arguments. Once the function is running, the following events take place:

- The function hits the

receivestatement. Given the process' mailbox is empty, our dolphin waits until it gets a message; - The message "oh, hello dolphin!" is received. The function tries to pattern match against

do_a_flip. This fails, and so the patternfishis tried and also fails. Finally, the message meets the catch-all clause (_) and matches. - The process outputs the message "Heh, we're smarter than you humans."

Then it should be noted that if the first message we sent worked, the second provoked no reaction whatsoever from the process <0.40.0>. This is due to the fact once our function output "Heh, we're smarter than you humans.", it terminated and so did the process. We'll need to restart the dolphin:

8> f(Dolphin). ok 9> Dolphin = spawn(dolphins, dolphin1, []). <0.53.0> 10> Dolphin ! fish. So long and thanks for all the fish! fish

And this time the fish message works. Wouldn't it be useful to be able to receive a reply from the dolphin rather than having to use io:format/2? Of course it would (why am I even asking?) I've mentioned earlier in this chapter that the only manner to know if a process had received a message is to send a reply. Our dolphin process will need to know who to reply to. This works like it does with the postal service. If we want someone to know answer our letter, we need to add our address. In Erlang terms, this is done by packaging a process' pid in a tuple. The end result is a message that looks a bit like {Pid, Message}. Let's create a new dolphin function that will accept such messages:

dolphin2() ->

receive

{From, do_a_flip} ->

From ! "How about no?";

{From, fish} ->

From ! "So long and thanks for all the fish!";

_ ->

io:format("Heh, we're smarter than you humans.~n")

end.

As you can see, rather than accepting do_a_flip and fish for messages, we now require a variable From. That's where the process identifier will go.

11> c(dolphins).

{ok,dolphins}

12> Dolphin2 = spawn(dolphins, dolphin2, []).

<0.65.0>

13> Dolphin2 ! {self(), do_a_flip}.

{<0.32.0>,do_a_flip}

14> flush().

Shell got "How about no?"

ok

It seems to work pretty well. We can receive replies to messages we sent (we need to add an address to each message), but we still need to start a new process for each call. Recursion is the way to solve this problem. We just need the function to call itself so it never ends and always expects more messages. Here's a function dolphin3/0 that puts this in practice:

dolphin3() ->

receive

{From, do_a_flip} ->

From ! "How about no?",

dolphin3();

{From, fish} ->

From ! "So long and thanks for all the fish!";

_ ->

io:format("Heh, we're smarter than you humans.~n"),

dolphin3()

end.

Here the catch-all clause and the do_a_flip clause both loop with the help of dolphin3/0. Note that the function will not blow the stack because it is tail recursive. As long as only these messages are sent, the dolphin process will loop indefinitely. However, if we send the fish message, the process will stop:

15> Dolphin3 = spawn(dolphins, dolphin3, []).

<0.75.0>

16> Dolphin3 ! Dolphin3 ! {self(), do_a_flip}.

{<0.32.0>,do_a_flip}

17> flush().

Shell got "How about no?"

Shell got "How about no?"

ok

18> Dolphin3 ! {self(), unknown_message}.

Heh, we're smarter than you humans.

{<0.32.0>,unknown_message}

19> Dolphin3 ! Dolphin3 ! {self(), fish}.

{<0.32.0>,fish}

20> flush().

Shell got "So long and thanks for all the fish!"

ok

And that should be it for dolphins.erl. As you see, it does respect our expected behavior of replying once for every message and keep going afterwards, except for the fish call. The dolphin got fed up with our crazy human antics and left us for good.

There you have it. This is the core of all of Erlang's concurrency. We've seen processes and basic message passing. There are more concepts to see in order to make truly useful and reliable programs. We'll see some of them in the next chapter, and more in the chapters after that.